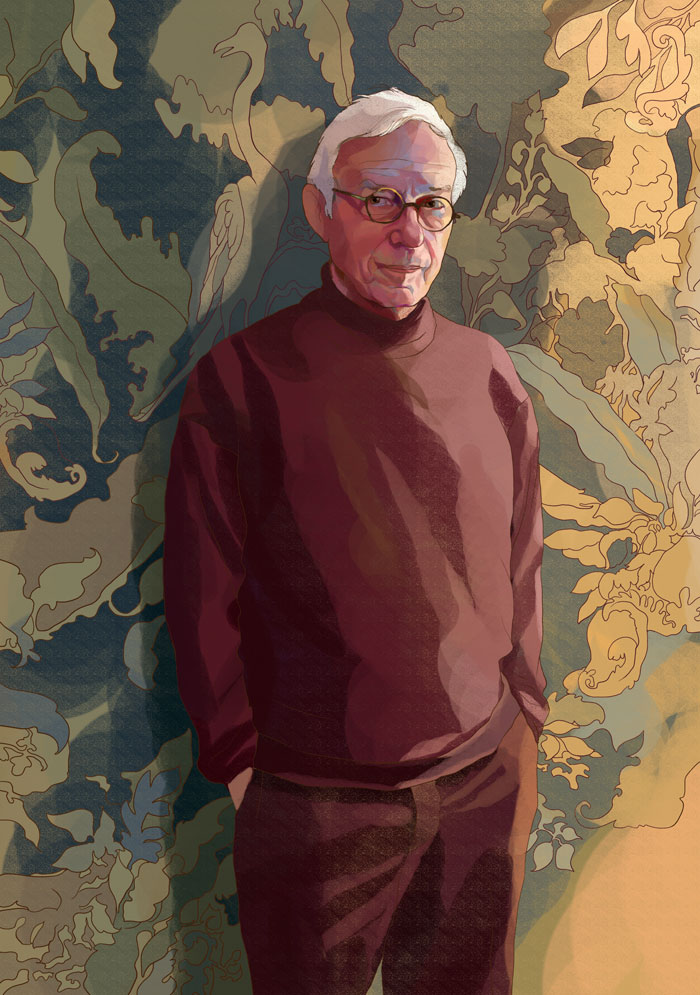

This is part of my series of profiles of illustrators and art directors, Art Talks.

R.O. Blechman, age 76, talks about what it's like to be highly visual and at the same time struggle to render what he sees. Over the course of more than 50 years, his passions for writing, animation and film-making have competed with illustration for his soul.

"As a kid, I had no interest in being an artist whatsoever. I wasn’t even a cartoonist except in high school and that was just to show off. It only occurred to me very recently that the only reason I went to the High School of Music and Art was that I was in love with my next door neighbor, a beautiful blond French girl who was an artist. I loved her. She painted her walls and had murals everywhere. She'd painted a donkey’s behind on the wall and the switch was where his ass was and she would ask me to, 'Turn on the lights please'. This, to me, was what art was all about!

"When I was in college at Oberlin, I was doing political cartoons, but it wasn’t art, it was really junky stuff. But I liked the idea of making political comments with my artwork. And there was a class ball, I guess you’d call it, and I remember that I decorated the entire hall with my own murals on paper, drawings of everything I loved; like I was crazy about the film Alexander Nevsky, so one mural was of that. But again, I never thought of myself as an artist.

"The Korean war was on, and after I got out of college I knew I’d be drafted. I didn't know if I'd be called up in a few months or a year, so I figured what the hell, I’ll just goof off and do what I enjoy doing, never thinking that it might be a career.

"I wasn't so much an artist as a cartoonist. My ideas were brighter and funnier than they were beautiful, because I just didn’t know how to draw well. And I wasn't, nor am I now, a natural artist. I am very visual, but I don’t have the hand. I work very, very hard to get things, which is probably true of many, many artists.

"I was shopping around my stuff and surprisingly selling it. I'm still amazed it sold, but the stuff was, again, very bright, because I’m clever, and very funny, because I had to compensate for the fact that it looked like hell. I've made a career based on the whole notion of breaking free of the text and interpreting it; I was on the cusp of that and that helped me a hell of a lot.

"Now this was a really crazy thing– in 1952 I did what’s now called a graphic novel, that was immensely successful. I mean, I couldn’t believe it. It was called The Juggler Of Our Lady and it was about a person who couldn’t do anything in life but juggle. I suppose I thought I couldn’t do anything in life but draw funny cartoons. The Herald Tribune, which was then comparable to The New York Times, gave it a full front page write-up. I mean, I was interviewed and blah, blah, blah and of course, it put my career in a tailspin, because I was too young to have that kind of success. For the next 10 years I didn’t come out with anything because I tried to copy what brought me the success, thinking that it was the book, not the person who made the book.

"Filmmaking has always been my real passion. When I was 19 years old and in college, I took a course in humor taught by a colleague of Buñuel, Augusto Centeno. And at that point, in a flash, it occurred to me that the future of our business is animation. I thought, 'This is what I have to do.'

"So, after college and my big book success, I freelanced a little and I went into the army for two years. And then, when I came out, my very first job was with an animation studio, Storyboard Studios. I was doing storyboards, but the storyboards were then given to artists to re-render because my stuff was considered unanimatable, because of the broken, jagged line I use.

"After that I was a freelance animator and illustrator, and in 1960, because I loved graphic design, and because I was bright and restless, I was part of a design team and we had our own studio for a short time, called Blechman and Palladio, which I loved.

"That broke up after a year. So I was doing commercials and a few books thrown in, and nothing much was happening in my career, but then I was lucky enough to produce an hour-long Christmas show for PBS called Simple Gifts. It was tremendously gratifying because I was able to use the artwork of many people I admire, like James McMullan and Seymour Chwast and Maurice Sendak. Being the producer and director, I did one of the segments, myself.

"After that I founded an animation studio called The Ink Tank. And that lasted up until a few years ago. I loved working with other artists, and I still do, as a matter of fact. And it’s fun to commission good stuff. I was able to do a few things of significance there, and the Stravinsky film, The Soldier's Tale, was the most gratifying of all the things I was able to do.

"I always felt that my skills, such as they are, are as much literary as visual – maybe even more literary than visual, because I always enjoyed language a lot. As for my drawing skills, if I work hard I can do very well. But I am very lazy, and I am not interested in art very much. I'm really not. I mean, I love it, but unless somebody says, 'Go do,' I don’t.

"I love both drawing and writing, but again, I tend not to draw unless I’m asked, but I write just because it’s immensely satisfying. I love it. I wrote a biography of Steinberg, that almost got published. I got a contract and an advance, but I ran into trouble with the Steinberg Foundation. It was tough, when it fell through, but I’m used to a lot of failures like that. I mean, I was blessed with a difficult childhood that prepared me for the freelance life. I had a psychotic mother: occasionally she’d lie on the floor and go into a spasm. I would run upstairs to the doctor who lived in our building, and he'd be eating and I’d say, 'Would you please go down, my mother is just lying on the floor screaming!' and he would finish his appetizer and main course and he would then finish his dessert. He knew my mother. She was a nut.

"My father was very cut off. Listen, if you were married to a crazy like that, you would be cut off, too. And he wasn’t a nice guy. He was a mean son of a bitch, particularly to my older brother. We were not the happiest family, but it prepared me for the freelance life and all the rebuffs that would happen. I've had my share of them and that's the way it goes.

"I've had some proud achievements in illustration, of course: some of my New Yorker covers were really very good and then the 10 years I did every single cover for a magazine called Story; I loved doing that stuff. It was fantastic. But I have not begun to fulfill my ideas about animation, which is my real passion. Even still, every few years, hey, I’ve got another idea for a feature, and it’s got to be done and I’m still hacking away at it. I’ll never stop."

Zina Saunders 2013