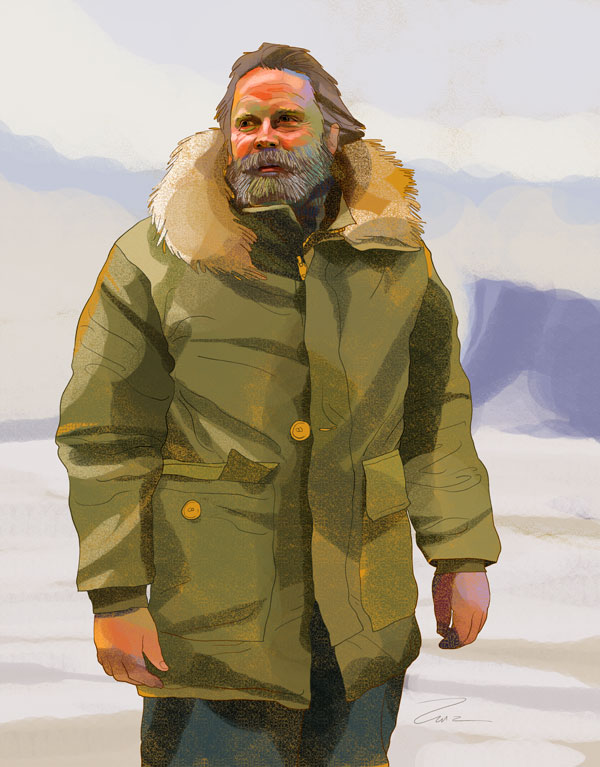

Jeff Bochart, Alaska

Jeff Bochart, 53, has spent most of his career teaching in tiny Alaskan schools, some of which were only accessible by bush plane.

"Back in 1979 I was in college in Bellingham, Washington and pretty much throughout the entire four years I was looking to get away from my home area in southwest Washington, which was relatives all over the place. I just wanted to make a break. It was the day before my last final and the assistant superintendent from the school district in Ketchikan, Alaska was vacationing down by car from southeast Alaska and he came to the placement center in Bellingham. He was just checking the placement list and, my last name being Bochart, I was near the top, and he invited me over to the hotel to visit. We talked about hiking and fishing and I don’t think hardly anything about my GPA and he said, 'Oh heck, you got the job.' So I went and finished my last final in Chinese and Japanese art and the next day I was on the plane heading to Ketchikan and truth to tell, I didn’t know where in the state it was!

"Ketchikan is big for an Alaskan town, with 14,000 people, and for my first seven years I was at a regular K-6 elementary school of about 500 kids. I was in the resource room, Special Ed, and in those years we’d pull the learning disabled students out of the classroom and work with them in math and reading.

"After that, my wife and I bought property about 300 miles north of that in Haines and that’s when I got into a little school, The Mosquito Lake School. It was a one-room school house, K through 8, with anywhere from 10 to 19 students.

"How do you keep kids at different age levels engaged? First of all, I learned very early on to throw away the lesson plan book; the best intentions written down in a lesson plan are often ruined by 10 o'clock. I had to pretty much keep it in my head and field things as they came up.

"Second of all, most people would be truly amazed at what little kindergartners can do when they can see what fourth and fifth graders are doing across the room. You’d be surprised at how soon they can sit down and be busy on activities for a half hour at a time. So it was that, and having the older students help teach the little ones. Of course you have to be careful with that, because you don’t want to be holding back the older kids too much, but let’s just say that it was that and then a lot of juggling and fielding things as they came up. And somehow it worked.

"I was at that Mosquito Lake School for 10 or 11 years and what you find after you have the same students for year after year, you almost get to teaching in circles. I covered reading and math okay, but when you're doing the sciences and social studies, you have to teach it in cycles and pretty soon I was repeating things to students I’d had for years.

"I needed a change and I had three years until retirement, but I didn’t want to move into Haines itself and teach at the town school there, so I offered to just leave home and the family and the property for those last three years and head to the Bering Strait School District, which is up in the Nome area. It's about the size of Minnesota and covers 12 or 13 villages. The school district has its own pilot, with its own twin turbo prop plane to fly teachers and administrators around for in-services and stuff, so it was very isolated. I was there three years, in three different villages.

"The first one was a place called Brevig Mission, which was a village that was slammed heavily by the influenza epidemic of 1918. See, what happened at Brevig mission is that the epidemic wiped out most all their elders, so basically it just cut the head off of the village. The folks there never really recovered; they were kind of lost, torn between cultures. I mean, you definitely had your skilled hunters and your excellent artists, but they kind of lost their identity. And teachers weren’t that well trusted, I guess you could say; there were some real hostile feelings, though a lot of friendliness too.

"After that I went to the village of Golovin, which was very different. In this village, you had a couple of dads who had been to Vietnam, and maybe a couple of the other folks went away to Anchorage and went to the University. You’d be amazed at what that little bit of worldliness can do to a whole village, in terms of its attitudes and how they look at things. It was really a neat place.

"My first night there, I was walking on the beach alone -- it hadn’t iced up yet -- and it was a seal harvest and I met two gals, upper middle aged, almost grandma type, and one of them said, 'Oh, you are the new teacher.' I said, 'Yes, I am.' And she said, 'Would you like some seal meat?' So I said, 'Sure.' And so here it came: plopped right into my hand was a big bloody hunk of seal meat, blood dripping all through my fingers. That's just what they did, they just handed it to me, plop, and I took it right home and boiled it up and it was great.

"My neighbor was an old Eskimo grandma named Maggie Olsen and her husband founded Olsen Airways, and their sons were all flyers. He died in a plane crash flying in bad weather and then later on one son and then another son crashed. She was a matriarch in the village. Her house was studded with antennas and her television always had the weather channel on and she was in tune with weather systems all across the whole northern hemisphere. She was just an amazing woman.

"I hadn’t been in the village long and someone had given me a beaver skin and I was attempting to scrape the fat off of it, out on my front porch, to figure out how to tan it. She saw me out there on the porch and called out that I didn’t know what I was doing. And indeed I didn’t, so I took it over and she brought out her old tools and I watched her work that hide over with her gnarly old hands and that was the beginning. After that there were many dinners with her and she was just one reason why that village was so special. There were so many nice people there and it was on the mouth of a beautiful bay about the size of San Francisco Bay, and was just a beautiful place.

"The third place was a very nice village, too, but it was the Big City in terms of the Bering Strait School District -- it had a population of about 800! The village was called Unalakleet, which means "Southernmost", because it was the southernmost place where the Inupiaq people still live -- Canadians call them Inuit, but in Alaska, they're called Inupiaq.

"Sometimes there would be gatherings of all the Special Ed teachers in the district, and to pick them all up, they'd start at one end of this huge area and fly from village to village until the plane was loaded up with eight or 10 people. If you were early on that route, you would get to fly over the frozen Bering Sea and land on all these islands, and see the musk ox bunched up or polar bear ... I mean seeing all that country from the air was just extraordinary; I really loved that very much.

"I'm coming away from teaching a bit broken-hearted though, because of Bush's 'No Child Left Behind' thing. Having to bring students up to a certain standard has spelled trouble for these kids out on the edge of the world. All the schools have to score a certain amount of what’s called annual yearly progress, and if you don't improve by a specified amount by a specified time, then you don't get funded. So you have to squeeze performance out of these students or you don’t get funding and schools close down. Our curriculum was dominated by raising the math, reading and writing scores and tests, tests, tests, and what fell away was music and native arts and we were just pushing these kids so hard to be competent in a world they may not even enter into.

"In Alaska there's a system where even though you are in retirement, you can get on a fill-in teaching list. What often happens in these remote areas is that people come to teach with the best interntions but find they don't like it. The first week of school is over and they're back on the plane home, so that leaves holes and the state placement system can go to a list of so-called veterans, and these people might fill in for a month or until Christmas or they might do the whole year. Again, I don’t like the pressure of what 'No Child Left Behind' has done, but there are those moments when you see the light come on for a student, when they understand something for the first time, or when time doesn't exist and the afternoon flies by ... so I’m considering putting my name on that list."

©Zina Saunders 2008–2014